Can an international taskforce curb corruption in Papua New Guinea?

Papua New Guinea is on the brink of being grey listed by the Financial Action Task Force. Photo: Pacific Security College

When Prime Minister James Marape addressed Papua New Guinea (PNG) on National Repentance Day in 2019, he called upon God to “curse” any PNG politicians or public servants – including himself – should they engage in corruption.

Six years later, at the same public event, Marape offered an apology and “withdrew” the curse. Instead, he asked God to remove him as the prime minister if ever he became a stumbling block to national progress.

In a country where 96 per cent of the population identifies as Christian and political decision-making is shaped by consensus-building and compromise, such appeals to divine and social forgiveness are not unusual. But these religious and cultural frames often come at the cost of building firm political will for sustained anti-corruption reform.

PNG is now at risk of being grey listed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in early 2026. The international body sets global standards across areas including anti-money laundering, counter-terrorist financing, and counter-proliferation financing (AML/CTF/CPF).

In a climate where domestic anti-corruption agencies, multilateral institutions and donor countries have consistently failed to hold PNG accountable, FATF could be the most powerful external driver of reform.

Funding failures and a lack of political accountability

Anti-corruption rhetoric in PNG has consistently failed to translate into substantive outcomes, as Marape’s comments at previous National Repentance Day events have illustrated.

He may have invoked divine accountability, but Marape is also the leader that engineered a constitutional amendment four months earlier that essentially shields him from another vote of no confidence before the 2027 election, entrenching his political survival.

Marape’s coalition also includes politicians accused of accepting bribes, engaging in controversial deals, and mismanaging millions of kina. Remember the 40 Maseratis purchased for the 2018 APEC summit? There are still 33 of these cars sitting idle in a shed in downtown Port Moresby, depreciating in value.

Institutional support for anti-corruption agencies has also mirrored this gap between rhetoric and action.

While funding temporarily increased after Marape replaced former prime minister Peter O’Neill in 2019, allocations have since declined. This replicates a pattern also observed when O’Neill succeeded former leader Michael Somare in 2011.

Even where appropriations appear substantial, the actual disbursement to anti-corruption agencies has consistently fallen short.

Meanwhile, prosecutions and dismissals of politicians have been in steady decline since the 2000s, despite mounting public concern over corruption. Agencies that demonstrated effectiveness, such as the Investigation Task Force Sweep, have been dismantled.

In practice, accountability in PNG remains weak and politically constrained. While donor countries and multilateral institutions have poured millions into strengthening anti-corruption capacity in the past five years, there are allegations corrupt funds are laundered to jurisdictions like Australia.

Impending international intervention

The Financial Action Task Force’s deliberation on whether PNG will be grey listed in 2026 represents a critical external accountability mechanism.

The Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG), of which PNG is a member, published the assessment of the country’s anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures in its 2024 Mutual Evaluation Report (MER). The assessment examined not only legislative compliance but also institutional vulnerabilities, the adequacy of preventive measures, and, most importantly, the effectiveness of enforcement outcomes.

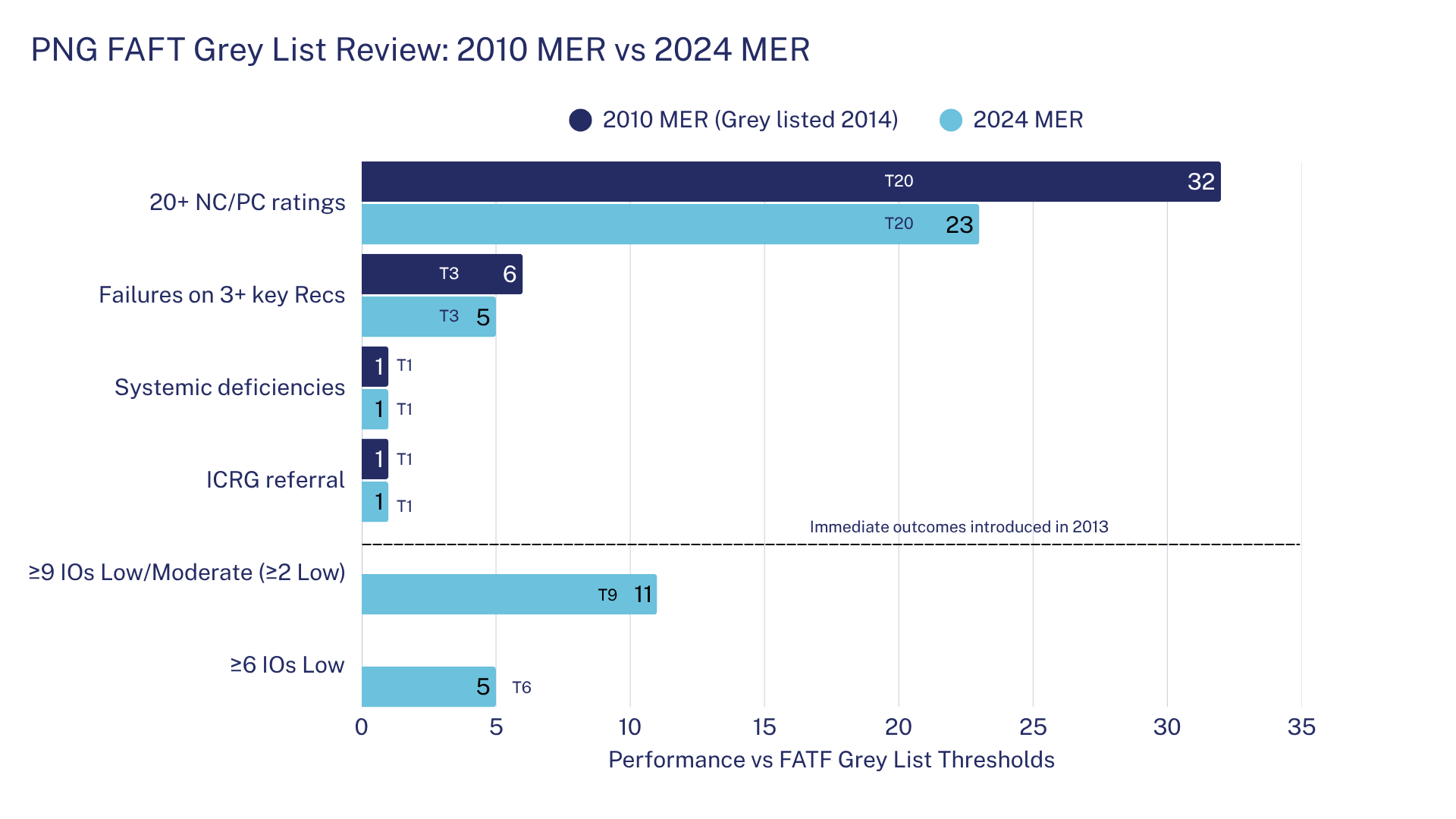

FATF applies minimum thresholds to determine grey listing or, in extreme cases, blacklisting. These include technical compliance failures –20 or more ‘non-compliant’ or ‘partially compliant’ ratings, or failures on three or more key recommendations; systemic AML/CTF deficiencies; and low or moderate effectiveness across nine or more ‘Immediate Outcomes’, with at least two rated ‘low’.

PNG exceeds all six of these thresholds. Its 2024 MER shows modest improvements relative to its 2011 evaluation but still places the country well below the required standards. Since introducing its first AML/CTF law in 2005, PNG has secured only five successful money-laundering prosecutions. Even if new laws are rushed through parliament, it is unlikely that prosecutions and enforcement outcomes will be scaled up in time to avoid grey listing.

Although incremental progress is evident when comparing PNG’s technical compliance and effectiveness ratings in the 2011 and 2024 MERs, the country continues to breach all technical compliance thresholds and has failed to meet effectiveness benchmarks introduced in 2013. As a result, PNG is highly likely to be grey listed again in February 2026.

Figure 1: Compliance (and effectiveness) vs grey list thresholds

Grey listing could have long-term benefits

In response to the APG’s 2024 report, Marape summoned integrity agency heads in May 2025, instructing them “in no uncertain terms” to work day and night to avert grey listing. This followed a joint statement from the Justice Secretary and the Bank of PNG Governor warning that “PNG will most likely be grey listed” and urging efforts to ensure the country would not remain on the list for long.

The scale of reform required is daunting. While Marape downplayed the challenge as “three or four areas”, more deficiencies must be tackled, especially the absence of prosecutions and asset confiscations. High-risk sectors identified in the 2017 National Risk Assessment, including logging, public corruption, fisheries, and tax evasion, remain virtually unaddressed.

Unlike other external assessments, FATF’s process compels government attention because public grey listing acts as soft coercion, mobilising global financial pressure and threatening exclusion from corresponding banking and investment.

Donor countries, by contrast, have struggled to exert comparable leverage in recent years, partly constrained by geopolitical competition and the strategic imperative of keeping PNG onside. FATF therefore remains the most powerful external driver of reform.

PNG’s current AML/CTF/CPF framework largely stems from reforms initiated after its 2014 grey listing, undertaken to secure removal in 2016.

If grey listed again in 2026, another wave of reforms will almost certainly follow. Indeed, several informants I interviewed during my PhD fieldwork between 2023 to 2024 suggested that grey listing might even be desirable as it will force PNG to confront corruption, which drains an estimated K4 billion annually. From this perspective, the long-term benefits of accountability outweigh the short-term economic costs.

Michael Kabuni is a PhD candidate at the Department of Pacific Affairs at the Australian National University (ANU) and a Pacific Security College PhD scholarship recipient.

Views expressed via the Pacific Wayfinder blog are not necessarily those of the Pacific Security College.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Read our publishing policy.