Navigating the next wave: how the Pacific can approach the evolving geopolitical landscape

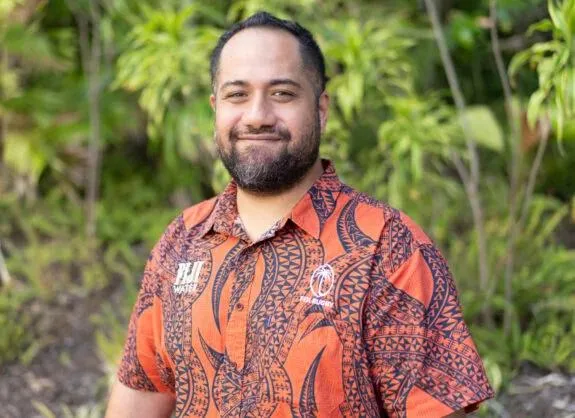

Regional unity is the Pacific’s greatest strategic asset. Photo: Pacific Security College

It’s clear that geopolitics will only get harder. As will navigating the strategic choices that come with strategic competition.

The Pacific has a long history of diplomatic agency and authority to draw on as it surveys the world around it and plots a course ahead.

Since the Pacific Islands Forum’s inception in 1971, the Pacific has been a diplomatic activist, advocating for its own interests on decolonisation, nuclear testing, the law of the sea and fisheries, and the existential threat of climate change.

More recently, the Pacific has charted a course through the Blue Pacific identity, 2050 Strategy for a Blue Pacific Continent, and Ocean of Peace Declaration to a stronger regionalism and collective identity, mission and purpose to prosecute and protect its interests.

Throughout, the Pacific has drawn strength from its unity and the Pacific Way, while leveraging moral authority, regional norms, and international law and diplomacy to maximise opportunity and manage risk.

As geopolitics and strategic competition continue to sharpen and intensify, the challenge will be not if the Pacific continues to engage but how.

Drawing on the lessons from the past and current foundations, five approaches stand out.

1. Anchoring engagement in regional unity

History shows that unity is the Pacific’s greatest strategic asset.

From nuclear testing to climate diplomacy, regional consensus amplified Pacific voices far beyond individual countries.

In an era of sharpening strategic competition – and increased pressure on individual countries to make difficult choices – maintaining cohesion can be an effective hedge against external forces.

2. Remaining grounded in civil society, culture and identity

Civil society has long been a key contributor to the identification and prosecution of Pacific strategic interests.

This traces to early years advocacy on decolonisation and nuclear testing, through to the more recent focus on climate change and strengthened regionalism shaped by Pacific identity and culture.

Civil society can help ground strategic decision making in Pacific interests as strategic competition puts pressure on individual countries to make difficult choices.

Anchoring decision‑making in Pacific identity and lived experience keeps a focus on human security, people and collective wellbeing. Photo: Pacific Security College

3. Prioritising human security

The Boe Declaration on Regional Security reframed security through a Pacific lens, focusing on climate, health, environment and human wellbeing.

This framing can help maintain focus on the issues of existential importance to the Pacific: climate change and sea level rise.

Importantly, it can help guide geopolitical choices, ensuring that partnerships and engagement strengthens – rather than dilutes and distorts – Pacific priorities.

4. Setting the rules before others do

The Pacific has repeatedly shaped global outcomes by setting regional norms first, then leveraging international law and multilateral institutions to reinforce them.

Proactive norm-setting can continue to be an important diplomatic tool as new security, technological and economic issues emerge.

The Ocean of Peace Declaration continues this practice by articulating expectations of behaviour in the region.

The proposal for a Pacific Seabed Stewardship Statement is a next early opportunity and could help countries agree on shared principles to guide future cooperation.

5. Engage widely, but selectively

The Pacific Way has always embraced dialogue and inclusivity.

But being ‘friends to all’ does not mean saying ‘yes’ to everyone, and not on every issue.

Strategic selectivity – grounded in transparency, regional unity and long-term interests – can play a critical role in enabling strategic choices and decisions in the Pacific’s interest.

Pacific and regional partners, including Australia, New Zealand and the United States, conduct a simulated disaster relief exercise in Samoa in 2025 as part of the multinational Exercise Pacific Partnership. Photo: Australian Department of Defence

Strategic selectivity

A number of areas present opportunities to work with both traditional partners and newer friends:

- Climate mitigation and adaptation, including renewable energy, resilient infrastructure and climate finance.

- Disaster preparedness and response, particularly early warning systems and humanitarian logistics

- Sustainable fisheries, where shared interests in long-term resource management should align.

- Health cooperation, building on lessons from COVID-19 and strengthening regional health security.

- Trade, connectivity and development finance, where projects are transparent, sustainable and aligned with national and regional plans.

Cooperation in these areas can deliver tangible benefits while reinforcing Pacific-defined goals and priorities.

Several areas lend themselves to closer cooperation with traditional partners alone:

- Security, policing and military arrangements, where the strategic choices are the most consequential.

- Debt-financed infrastructure, where long-term fiscal sustainability and sovereignty issues warrant careful safeguards.

- Critical minerals, AI and digital infrastructure that carry sensitivities around privacy, resilience and sovereign control.

- Critical supply chains and assets, which risk concentration and loss of sovereign control.

- Regional institutions, governance and decision making where the risk of undermining regional consensus and decision making is high.

Navigating the future

There is no doubt that strategic competition will only become more difficult to manage.

But the region has a proud tradition of diplomatic agency to draw on in the prosecution and protection of its interests.

And the Pacific can play to its strengths – unity, culture and identity; defining its own priorities; setting its own rules; determining its own partnerships – to help navigate the difficult strategic choices that lie ahead.

Ben Burdon is a former Australian diplomat and senior public servant.

This is the final article in a series exploring lessons learned by the Pacific Islands Forum since 1971, and how they can support the region to manage emerging geopolitical challenges. Read the first and second articles.

Views expressed via the Pacific Wayfinder blog are not necessarily those of the Pacific Security College. Read our publishing policy.