Shaping the second wave of Pacific diplomacy

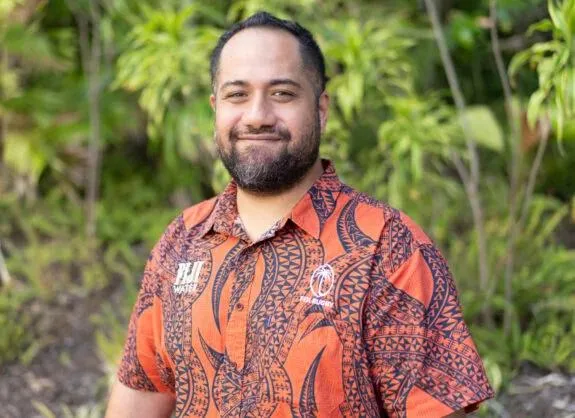

Leaders at the 54th Pacific Islands Forum Leaders’ Meeting in Solomon Islands. Photo: Pacific Security College

If the establishment of the Pacific Islands Forum in 1971 marked the first wave of Pacific diplomacy, the 2025 declaration of the Blue Pacific Ocean of Peace marks a second.

The Blue Pacific

In 2012, former Kiribati President Anote Tong challenged the Pacific to chart its own course, assertively and in its own voice, speaking for all civil society, business and government.

The Forum took up the challenge and the 2017 Leaders’ Communique first articulated the idea of the ‘Blue Pacific’ as a collective identity – a way to reframe regionalism around shared stewardship of the ocean, geography and culture.

By 2018, the narrative had become central to how the Forum described its mission and purpose. Leaders declared that the Blue Pacific identity was both the driver and vehicle for collective action, reaffirming the need for unity and leadership in addressing challenges that no single member could face alone.

Climate change was reaffirmed as the “single greatest threat” to the region’s livelihoods, security and wellbeing, and the Blue Pacific was positioned as the foundation for stronger international engagement and advocacy.

Importantly, the Blue Pacific narrative was not just rhetoric.

It marked a shift from issues-based cooperation and advocacy – as seen in earlier Forum diplomacy – to a more strategic and identity-based regionalism.

Regional unity vs strategic competition

Sharpening geopolitics became the new normal, across the world and in the Pacific.

Traditional partners doubled down on longstanding ties and new friends came to the fore.

While the increased interest brought significant opportunity, it was not without challenge. Leaders were often forced to make choices, testing the region’s ‘friends to all’ approach and one of the fundamental principles of Pacific diplomacy.

By 2019, Leaders’ Communiques reflected the increasing concern over the geopolitical rivalry playing out on their doorstep.

The Forum’s task became one of balancing strategic risk and opportunity, managing new friends and traditional partners, and maintaining the regional consensus that had underpinned Pacific diplomacy for 50 years.

Leaders reaffirmed regional unity as the region’s greatest asset, stressing that the Blue Pacific identity must underpin all external partnerships.

They committed to a “collective approach to regional security” through the Boe Declaration Action Plan, ensuring that human security, climate change and environmental integrity remained central to the region’s conceptualisation of security.

The Blue Pacific marked a shift in tone – measured but assertive. The Pacific welcomed engagement but on its own terms and in line with its own priorities and values.

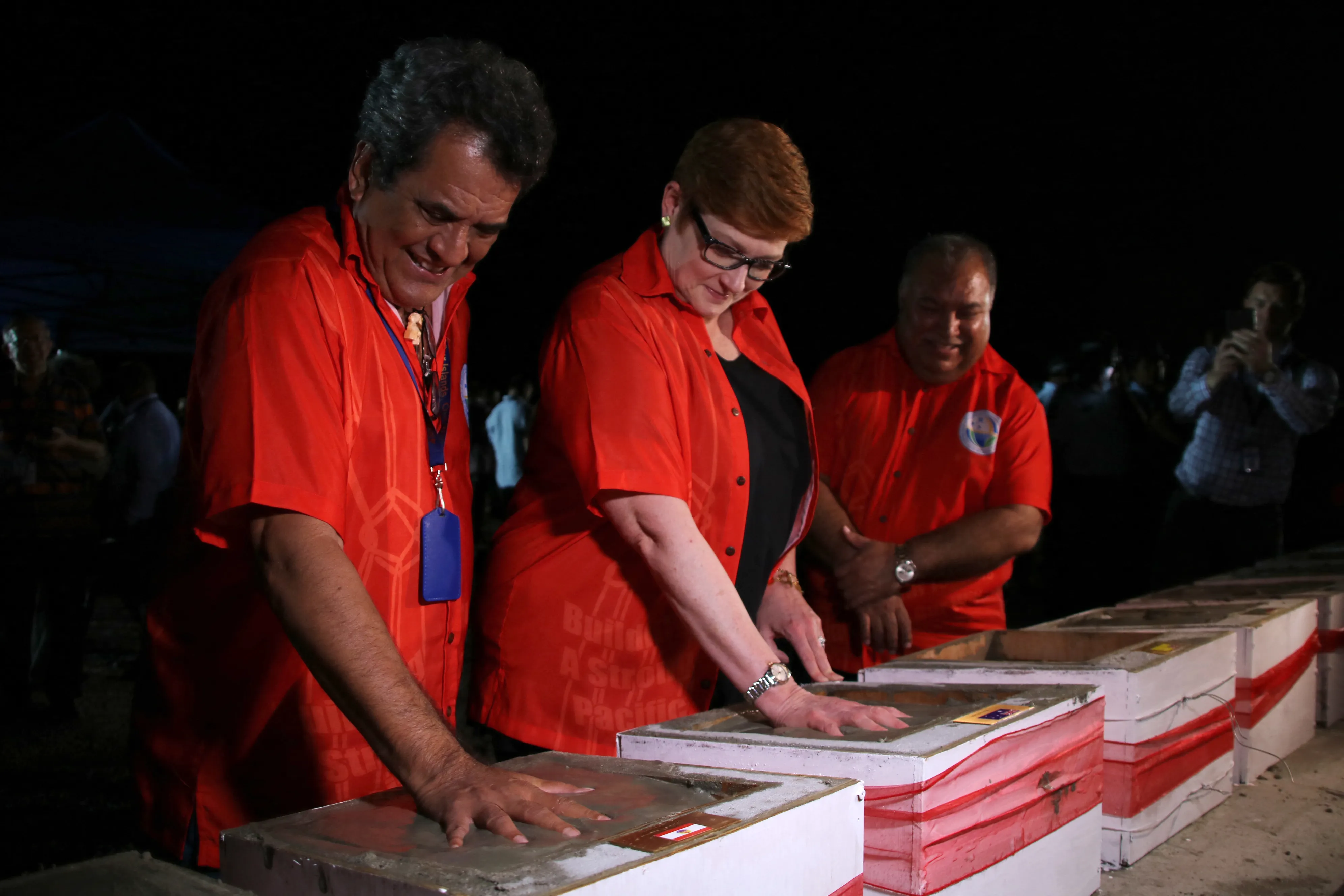

Former President of French Polynesia Edouard Fritch and former Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne leave commemorative handprints to mark the signing of the Boe Declaration in 2018. Photo: Mike Leyral/AFP

Towards a strategy for the Blue Pacific

As the world emerged from the global shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders doubled down and agreed on the need to build strategy, structure and organisation around the Blue Pacific narrative.

The 2050 Strategy for a Blue Pacific Continent was commissioned to guide and embed regional cooperation for the next three decades.

In the 2021 and 2022 communiques, leaders described the strategy as a “platform for collective action” that would broaden, deepen and strengthen Pacific solidarity and ensure that regional institutions were fit for purpose.

The 2050 Strategy, adopted in Fiji in 2022, set out a vision for a “resilient Pacific region of peace, harmony, security, social inclusion and prosperity, that ensures all Pacific peoples can lead free, healthy and productive lives”.

The Blue Pacific Ocean of Peace

As the geopolitical winds continued to blow hard in the region, the 2025 Blue Pacific Ocean of Peace Declaration proclaimed the vision and expectation of a “resilient Pacific Region of peace”.

The Ocean of Peace was a natural evolution of the Blue Pacific identity and 2050 Strategy, reaffirming that the region’s strength lay in its unity and the Pacific Way.

It was a clear declaratory statement of diplomatic intent and expectation, directing external actors to respect and engage in ways consistent with the region’s own vision for peace and security.

From consensus to strengthened regionalism

The Blue Pacific, 2050 Strategy and Ocean of Peace trace the evolution of the Pacific Way from consensus and collaboration to strengthened regionalism and collective identity, mission and purpose.

Where once unity was key to negotiating on the international stage, collective identity, consensus and solidarity have since taken on their own strategic importance, aligning ends, ways and means.

The Blue Pacific narrative gives coherence to this approach.

The 2050 Strategy provides architecture and institutional framing.

The Ocean of Peace Declaration articulates geopolitical purpose.

Each reflects a Pacific that continues to navigate the currents of global politics with its own moral compass – leveraging identity, culture, geography, regional norms and international law and diplomacy to protect and advance its interests.

Ben Burdon is a former Australian diplomat and senior public servant.

This is the second in a series of articles exploring lessons learned by the Pacific Islands Forum since 1971. Read the first article.

Views expressed via the Pacific Wayfinder blog are not necessarily those of the Pacific Security College.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Read our publishing policy.