There is no security without development, anything else is a distraction

Reclaimed land in Funafuti, Tuvalu. Photo: Pacific Security College

The region’s evolving discussions about a proposed ‘Ocean of Peace’ should not dilute or distract from existing commitments under the Pacific Islands Forum’s 2018 Boe Declaration on Regional Security.

Advancing Pacific human security has seen slow progress in over a decade, compounded by a deepening climate crisis. The region cannot afford protracted diversions brought about by strategic competition or reactions to partner geopolitics. Instead, amplified focus on implementation of existing Pacific commitments is needed to regain momentum on sustainable development.

Persistent human insecurities destabilise prospects for Pacific peace

Development and security are two sides of the same coin. This point was underscored by Niue’s Prime Minister Dalton Tagelagi in July 2025 at the Pacific Regional and National Security Conference. “Security is holistic. It is the whole person. It is a whole community. It is a whole country, and it is a whole region. Security is leaving no one behind,” Tagelagi said.

But, unfortunately, our region is leaving many of our people behind.

The most recent Quadrennial Pacific Sustainable Development Report (2022) estimates that one in four Pacific islanders live below their respective national basic needs poverty line. Poverty of opportunity is worsening and deepening socio-economic inequalities are real concerns for all countries. Gender equality remains significantly underfunded. Climate change impacts multiplier effects on a range of human security areas, such as food, water and health security post-disasters.

Progress depends on action that addresses insecurities across the Pacific region. Photo: Pacific Security College

A tug of war to dominate Pacific security narratives

It is particularly concerning when regional partners are willing to invest significantly in traditional security activities, yet support for Pacific islands’ most pressing development needs is nominal. The 2025 cuts to the USAID budget, both bilaterally and via multilateral bodies, for example, will approximately cost the region upward of US$249 million annually. In contrast, US military expenditure and security cooperation in the Pacific remains healthy, with a bilateral PNG-US defence deal valued at US$864 million over 10 years.

The Boe Declaration is an important step in closing the distance between Pacific island countries’ development needs and prospects for peaceful and secure region. It provides an important regional compass during an era of marked strategic competition and heightened geopolitical interest in the Pacific Ocean. The Boe helps maintain focus on a Blue Pacific strategic security narrative.

In 2025, this focus is needed to maintain control over a comprehensive Pacific security agenda that leaves no one behind. This means being selective about where to invest valued political energy on regional security priorities, and not becoming “a chessboard for global competition”.

Retaining Pacific control of the regional security agenda also means saying ‘no’ to, or pausing, partner geopolitics or new initiatives that distract from consolidating efforts on existing regional commitments through Boe, and a plethora of other regional strategies and roadmaps.

The recent, increased frequency of new security-related announcements and proposals in the region is no coincidence. Whether a Pacific Policing Initiative to support multi-country response capability, a mass donation of police patrol boats or a possible ‘Ocean of Peace’ to mediate growing geopolitical tensions in the region, these all ostensibly contribute to the overarching objectives of the Boe Declaration and its peace and security pillar companion in the Pacific 2050 Strategy.

But they can also contribute to the crowded complexity of Pacific security, at the expense of Pacific peoples’ more pressing existential, livelihood and social protection needs.

This raises the question: how can there be a peaceful and prosperous Pacific region if our people’s insecurities are not addressed?

Closing the development-security gap – can the Ocean of Peace concept assist?

It’s time to shift the dial from declarations of policy commitments to more concrete, appropriately resourced actions that address persistent human insecurities throughout the Pacific region.

Securitising climate action and human development is one way to pragmatically leverage the strategic competition in the region to spotlight areas of much-needed development finance. For example, Solomon Islands successfully leveraged geopolitical duels between Australia and China to secure internet cabling finance.

However, the paradox of securitising elements of Pacific island life – as Pacific scholars Romitesh Kant, Vehia Wheeler and Mereoni Chung argue – is that sustainable peace must be found through people-centric, and people-driven approaches, not through the hard, militarised power of surveillance technology, weapons or soldiers and border police.

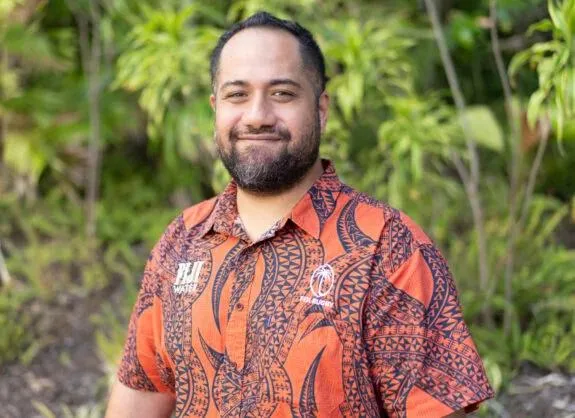

Prime Minister of Fiji, the Honourable Sitiveni Rabuka, proposed the Ocean of Peace concept in 2023. Photo: Pacific Security College

The allure of the Ocean of Peace’s evolving concept is its potential to strike the right balance between development and security attention. While the concept itself has produced polarising debates about de/militarisation and justice for unaddressed legacies of colonialism and nuclear testing, for example, some see opportunity to define a new regional rules-based order and to re-assert Pacific partnership principles.

These perspectives all have merit, but raise new questions: why are these long-standing issues still unresolved and will an Ocean of Peace catalyse overdue action or divert policy attention?

This dialogue comes at a time when the Pacific is also being crowded by introducing additional bureaucratic processes of its own making. Some participants at the July 2025 Pacific Regional and National Security Conference called for more action on implementing existing regional initiatives rather than chasing new, potentially duplicative, proposals.

Achieving sustainable peace through human development requires a refocus on consolidating regional resource mobilisation and addressing structural drivers of Pacific insecurities.

The Ocean of Peace provides a welcome spotlight that returns attention to Pacific values and understandings of peacefulness.

But beyond that it is a political distraction from the genuine, urgent calls to fully implement the commitments of national and regional security strategies and action plans, themselves aligned closely to the region’s sustainable development priorities.

The Pacific Island region’s population will double by 2050. More than half this population will be under the age of 24. The human and economic development needs of present and future generations, the food, water and land security needed to nourish and sustain populations, and the protection of our environment – this is where our regional focus must remain.

The Boe Declaration already serves to close the development-security gap and assists the region to navigate an uncertain future while leaving no one behind. Why would we want further distraction from resourcing this important task?

Anna Naupa is a Pacific policy and development specialist. She is currently completing a PhD at the Australian National University.

Views expressed via the Pacific Wayfinder blog are not necessarily those of the Pacific Security College.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Read our publishing policy.